As spiritual carers, we often find ourselves standing at the threshold of mystery. A person’s suffering, their questions, their silence—all invite us into something deeper than diagnosis or doctrine. But how do we, as spiritual carers, respond wisely and compassionately without falling into a patchwork of disconnected theories?

This is where John Vervaeke’s 4P knowing might help.

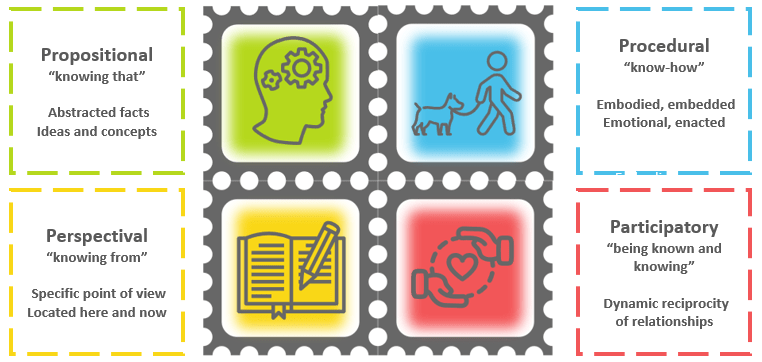

Philosopher and cognitive scientist John Vervaeke offers a framework that helps us hold the complexity of human experience with integrity through the dimension of four kinds of knowing: Propositional, Procedural, Perspectival, and Participatory. These categories explore the length, breadth and depth through the unfolding experience of time.

Being aware of these dimensions allows us to subtly tease apart the laminated layers of experience, which are much more than just academic categories—they help us attend to the whole person.

1. Propositional knowing: held in the head

This is the realm of facts, beliefs, and ideas—the “head” knowledge. It’s where theology and philosophy live, where doctrines and theories are debated. But propositional knowing has its limits. It is a distillation of lengthy deliberations stripped of their particularity—the map, not the terrain. Propositions orient us and set our direction, but they lack specificity. They rarely answer the individual cries of “Why did this happen to me?” or “Where is God in this?”

When someone is in crisis, their beliefs may no longer make sense. They may feel betrayed by the very truths they once held dear. This is the terrain of cognitive dissonance, where what we believe and what we experience no longer align.

In these moments, explanations, shallow solutions or fast resolutions fall short. We work with the “is,” not the “ought.” We honour the real, not the ideal. We are listening for the deeper questions beneath the surface, knowing that some truths can only be lived, not solved.

2. Procedural knowing: held in the body

Procedural knowing is embodied. It’s the knowledge of the body, of habits, of rituals, of the unspoken. It may take the form of absent-mindedly pouring a cup of tea, or the pattern of folded hands to receive communion, the rhythmic pounding of the pavement on a run or the instinctual understanding that accompanies bike riding. Or, it might take the form of intuition or the sensation of having hit the car’s brakes before you even saw the child running out between parked cars.

This type of understanding is particularly crucial in trauma-informed care. The body remembers what the mind cannot articulate. Emotions, sensations, and gestures often speak louder than words.

Here, spiritual care becomes accompaniment. We meet people in their rituals, their silence, and their tears. We use poetry, music, liturgy, and touch (when appropriate) to communicate love and safety. We recognise that even those who cannot articulate their faith may still live deeply spiritual lives.

3. Perspectival knowing: held in the story

Perspectival knowing is about context. It’s about how people see the world, how they interpret their experiences, and how their stories shape their identity.

This is where narrative becomes a powerful vehicle. By helping people see their stories in a different light, we invite them to see their lives through new lenses.

We draw on metaphors, parables, and even paradoxes to help people find meaning. We honour their “horizons of significance,” as philosopher Charles Taylor puts it, and gently expand them. We don’t impose our perspective—we help them discover their own.

4. Participatory knowing: held in the heart

Finally, participatory knowing is relational. It’s the “I-Thou” space described by Martin Buber, where we meet each other not as problems to be solved, but as sacred beings to be encountered.

This is the deepest kind of knowing. It’s not about information—it’s about transformation. It’s about being with someone in their suffering, not above it. It’s about mutual presence, shared vulnerability, and the sacred dance of trust.

In participatory knowing, we don’t just offer care—we become part of the care. We pray together, we cry together, we sit in silence together. We become companions on the journey, not just guides.

Why it matters

In spiritual care, no single kind of knowing is enough. Wisdom engages all dimensions of knowing. We need the clarity of the head, the habits and intuitions of the body, the insight of the story, and the intimacy of the heart.

This is especially true in spiritual care, where the boundaries between life and death, hope and despair, justice and injustice, and faith and doubt become porous. Here, the spiritual carer must be fluent in all four languages, able to move gently between them as the moment requires.

The content of the post is drawn from pages 16-18 of a journal article I wrote in 2022. The rough draft was created from the article with the help of an AI assistant, and then I refined it personally. The 4P infographic draws on summarised material from the article by Vervaeke and Ferraro.