A century ago, Dr Richard Cabot issued a plea that still resonates: chaplains need more than theory—they need a clinical year. Not just books and lectures, but bedside learning—where life is raw and questions are real. Anton Boisen called patients “living human documents.” Those words remain luminous. They remind us that formation is not abstract; it happens in the presence of suffering, in the fragile spaces where meaning frays.

When I speak of Supervised Group Reflective Practice, I mean formation groups where pastoral encounters are brought for honest reflection and feedback—where peers ask the questions we’d rather avoid, and supervisors hold silence until insight comes. It’s the rhythm of noticing, wondering, and seeing. This practice shapes future encounters with new perception and awareness. And it’s not just for healthcare chaplains; it matters wherever professional spiritual care is offered—aged care, defence forces, mental health, prisons, and more.

Cabot and Boisen built their training model on the emerging discipline of social work, using case studies as the foundation. That approach gave rise to Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE), now the standard in many countries. The Association for Clinical Pastoral Education (ACPE) describes CPE as supervised encounters with people in crisis, grounded in feedback from peers and educators. The method is simple and profound: learn by doing, reflect in community, then return with practice reimagined.

Why does this matter? Because spiritual care is more than theory—it’s practice. Practice that works at the edge of suffering, where people search for words and those who care carry weight they cannot name. Reflection in community teaches us to stand there without flinching, to listen beneath the surface, and to remain in the tension without collapsing the space with quick fixes—to notice and wonder before seeing.

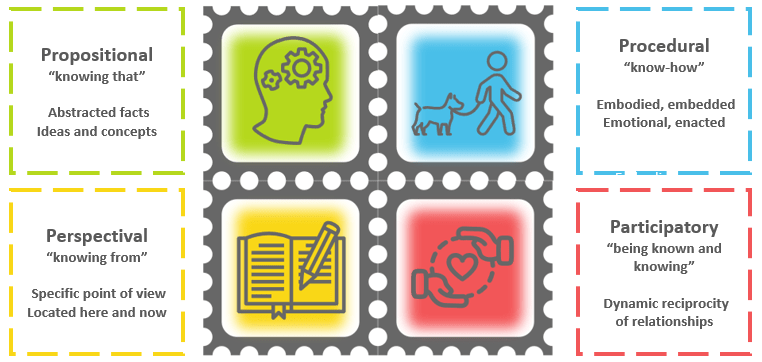

Spirituality is a dynamic, relational dimension of life. It shapes how people experience, express, and seek meaning, purpose, and transcendence. It includes how they connect—to themselves, to others, to nature, to the significant and the sacred. Good spiritual care improves quality of life, coping, and resilience. But competence is key. Chaplains need to move seamlessly between two principal modes of care: the reflective presence of compassionate listening and the reframing processes that help people find new meaning. They need to know which mode they’re in, when they shift, and why. Frameworks like the Living Wholeness CURE model (Dr John Warlow) or the Attuned Listener (Dr Jackie Perry, Columbia University) can scaffold these encounters. But these skills don’t come from books alone—they come from repeated practice, held and examined in the crucible of community reflection.

Here’s the challenge: chaplaincy training is increasingly embedded in university programs. That brings strengths—scholarship, research literacy, consistency. These matter. But as curricula grow, links to robust practical training become thinner. We risk forgetting John Dewey’s maxim: “We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.” A practicum that simply places a trainee in a workplace isn’t enough. True learning requires a disciplined program of supervised thought, reflection, and evaluation.

Practicums without supervised group reflection expose both trainee and care recipient to risk—care that lacks safety, care that may be ineffective, and trainees repeating the same mistakes. We see the need, yet feel the drift toward academia. Reflective practice groups are labour-intensive and costly, and they don’t fit neatly into funding models. In Australia, chaplaincy formation risks becoming over-theoretical. We need balance—embodied experience and communal wisdom alongside theology and pastoral theory. Integration, not substitution.

For years, a 400-hour unit of Clinical Pastoral Education or equivalent has been considered the minimum practicum for chaplaincy in hospitals, prisons, and defence forces. For Christian chaplaincy, this practicum sits alongside theological studies—neither replacing the other. Education providers have struggled to implement these sustained supervised practicums, often omitting structured reflective practice groups. The result? Programs that miss the heart of formation.

We stand at a crossroads: chaplaincy education risks becoming overly theoretical, while the need for embodied, reflective practice remains urgent. How do we reclaim what Cabot and Boisen knew—that formation happens in the crucible of experience and reflection? In Part Two, we’ll explore practical steps and models that can help us bridge this gap.